“And fornicate my bleeding life away.”

I have been coding some crude MaxMSP patches, both for algorithmic piano composition, and for pedagogical purposes (for my advanced students). I have also been thumbing through many of my books, which is way more fun that looking at a computer screen with decent pr0ns. Some such books: one concerning Μάχη τῶν Θερμοπυλῶν, http://www.amazon.com/Fathers-Daughters-Their-Own-Words/dp/0811806197, Sonic Warfare: Sound, Affect, and the Ecology of Fear (Technologies of Lived Abstraction) with the following review:–

(The review is evidently responding to a troll.) At least the title of the book is honest, and the material too, though I am so dumb it is probably about how to eat recently killed game with delicacy (but no relish), on polishing Rolls Royce engines while they are running, on contradancing. I have bought 100 or so new books in the past six months, such is the intrigue I have with fonts of wisdom, the smell of paper, nice layout, always from major presses. I love books and paper and manuscripts; I used to have a part-time summer job (1998) at Houghton Library at Harvard University. That’s where the rare books and manuscripts are kept, real white glove and glass rod material.

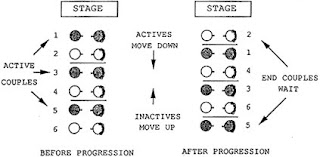

And speaking of iDance Contra’s “canned hell”: am I, trying not to disturb nature by opening that “can of hell” by breeching Pauli’s exclusion principle, and instead being more inclusive, reading about dancing, ... censored, though, lightbulb! Something just clicked! It is popular at places like Harvard and BU because the patterns resemble predictable flow in fluid dynamics! And that is all about lovin’. Here are some pictures, and this ain’t the 1/10th of it:–

And here are some excerpts. It really must be about fluid negotiating bends and changes of diameter of pipe, kind of a Bernoulli thing. Here is part of the derivation of the Bernoulli equation for incompressible fluids:

I get a hint, looking at that, that someone likes their sativa, but seriously, like, with gravity.

http://www.cdss.org/elibrary/dart/appendix_a.htm

http://www.cdss.org/elibrary/dart/appendix_b.htm

And some incredible information about flow in contradance:–

[Retrieved from http://www.cdss.org/elibrary/dart/aesthetics_1.htm on 20110227-1914.]

AN AESTHETIC OF CONTRA DANCING

The responses given by my informants in answer to the question “What makes a good dance?” can be divided into a number of clusters of criteria, each of which I would like to discuss in some detail. These clusters include the “flow” of the dance, the choice of figures and formations used in the choreography, the complexity of the dance, the social interaction that takes place within the dance, the degree to which the dance moves conform to the expectations of the dancers, the fit of the dance to the music, the physical activity level of the dance, and the quality of specialness or uniqueness exhibited by a dance.

FLOW

The most common short response to the question, “What makes a good dance?” was “good flow.” The concept of “flow” seems to refer predominantly to the transitions between the dance figures rather than to the figures themselves, and it relates to how smooth these transitions feel to the dancers. Here are two summary statements from my informants that give an idea of what is meant by this term, “flow”:

If the dance is smooth, it means that the transition from one figure to the next is easy to achieve. You do not ever have to turn the hard way. You don’t ever have to stop, literally stop in your tracks, and backtrack to do something else. Everything flows into the next thing, so you are eternally walking forward. (Park 1990)

The term “flow,” as used by my informants, has both physical qualities which have to do with the laws of physics, and nonphysical qualities which have to do with the expectations of the dancers and the degree to which they perceive the dance as “making sense.”

The physical component of “flow” concerns the motion of the body. In a dance with good flow the dance sequence avoids transitions where the dancer must change his or her momentum suddenly through either a change of direction or a change of dancing speed. (“Suddenly” is an important qualification, since many dances have either a full stop, or an assisted change of direction through an “allemande” or other strongly connected figure performed with another dancer.) If such a change of momentum is easily anticipated and can be done comfortably, it may not disrupt the flow of a dance. An example of a comfortable change of momentum might be the change from a “circle left” to a “circle right,” a transition which is common and anticipated and for which dancers have learned to adjust their footwork to make it smooth. An example of an uncomfortable change of momentum might be an “allemande left” followed by a “circle left,” in which the dancers must change from a forward counterclockwise motion to a sideways clockwise motion, requiring both a change of body position and a change of direction. Bad flow may also result from movements that are difficult because the hand that is needed is not free. Steve Zakon gives an example:

...

It is possible to have too much flow in a dance, especially when the choreographic sequence includes a lot of circular motion. A dance with too much flow can leave the dancers either disoriented or dizzy. Ted Sannella comments on this phenomenon:

...

In the composing of contra dances with good flow, conservation of momentum is an important principle. The movements work better when one takes advantage of the momentum already established in a previous figure, because the dancers do not have to work as hard to perform the dance. In particular, when rotating figures move into other rotating figures, the direction of rotation should not be reversed. Gene Hubert elaborates:

The conservation of angular momentum may produce acceleration and deceleration within the dance. For example, going from a “circle” into a “swing” involves an acceleration of movement, because as two dancers pull closer together for the “swing,” the conservation of momentum results in their going faster, an exciting and pleasing effect.

One way for the dancers to change directions without disrupting the flow of the dance is to use assisted changes of direction, as noted above. An “allemande,” for example, can be used to send two dancers in the opposite directions from which they came, without their having to stop or turn around. Dan Pearl gives an example:

The dance composer must be careful in the use of the directions “right” and “left” if the dance is to flow well. If many dancers are doing a movement together it is not likely to be confusing, but if a single dancer must make a split-second decision between right and left, some dancers will be confused, and the flow of the dance will be disrupted by their hesitation. John Krumm has noticed this problem:

Another guideline offered for the composing of dances with good flow is that the last move of a dance must flow well into the first move. This is because when the dance is actually performed by the dancers, the dance is repeated perhaps fifteen times, and the transition from the last move to the first one becomes just as important as any of the other transitions. Ted Sannella emphasizes this point:

The last principle of flow discussed by my informants comes out of the problem of too much flow discussed above. In order to avoid a dance being disorienting or dizzy, the dance composer needs to insert moves which do not revolve, to break up the circular flow of a dance which contains a lot of “swings” and “circles.” Straight line movements such as the “forward and back” figure or a “down the center and back” figure will serve to break up a dizzying circular flow, as will any kind of “balance” figure.

[Retrieved from http://www.cdss.org/elibrary/dart/changes.htm on 20110227-1907.]

TABLE 2. CHANGES IN CONTRA DANCE CHOREOGRAPHY

FORMATIONS:

1. The triple formation and the proper formation are used less frequently.

2. The improper formation and the Becket formation are most commonly used.

SYMMETRICAL ROLES:

1. There is less distinction between the roles of the active and inactive couples.

2. Terminology has been altered to reflect this change.

FIGURES:

1. The use of the “swing” has increased.

2. Fractional figures are common.

3. Figures danced on the diagonal are being used.

4. Borrowed and invented figures have been added to the repertoire.

5. “No hands” figures have become more popular.

6. Strongly connected figures are used to facilitate good flow.

7. The use of figures requiring unequal roles has declined.

TRANSITIONS:

1. The sequence “down the center and back” and “cast off” has declined in use.

2. Figures that cross the set and return are now used more often in their half form.

3. Transitions are designed to build momentum for vigorous dancing.

COMPLEXITY:

1. Sequences are more complex.

2. Figures of shorter duration are common.

3. Dance movements are faster and use closer timing.

MULTIPLE PROGRESSIONS AND END EFFECTS:

1. Dances have been composed that progress the dancers more than one place in a single round of the dance.

2. Both single and multiple progression dances may require dancers to dance outside their minor set of two couples.

3. More complicated choreography has resulted in more complex adjustments that must be made at the ends of the set.

NUMBERS OF DANCES:

There are many more dances in circulation now.

******

I have so many books to write about, and interests, now that I made a major breakthrough. It might just be a TP in my ~life. I talked about TP in this blog or the other. And, especially pertinent....

I see the Coen brothers have a new cinematic experience awaiting me. Yes, just for me. No Country for Old Men was quite something. From Wikipedia (yawn):–

Javier Bardem as Anton Chigurh, a hitman hired to recover the missing money. The character was a recurrence of the “Unstoppable Evil” archetype found in the Coen brothers’ work, though the brothers wanted to avoid one-dimensionality, particularly a comparison to The Terminator.[7] The Coen brothers sought to cast someone “who could have come from Mars” to avoid a sense of identification. The brothers introduced the character in the beginning of the film in a manner similar to the opening of the 1976 film The Man Who Fell to Earth.[8] Chigurh has been perceived as a “modern equivalent of Death from Ingmar Bergman's 1957 film The Seventh Seal.”[9] Chigurh's distinctive look was derived from a 1979 photo from a book supplied by Jones which featured photos of brothel patrons on the Texas-Mexico border.[10] After seeing himself with the new hairdo for the first time, Bardem reportedly said, “I’m not going to be laid for three months.” Bardem signed on because he had been a Coens’ fan ever since he saw their debut, Blood Simple.[11]

The latter film is one of my favorite films ever, and I think while watching (it for the tenth time) that I received my first success handjob. Quite startling. Closely behind Blood Simple is the candid O Brother, Where Art Thou?. I would certainly not label it a comedy. And, yes, the parallels with Homer’s Odyssey are in plain sight. I am sure many people say that. I bet many of them haven’t read Homer’s Odyssey, even in translation. They might just know about Circe, the Sirens, Calypso, and Trojan Horses. No, that’s the Iliad.

On my other blog I am singing of song, about

I have been coding some crude MaxMSP patches, both for algorithmic piano composition, and for pedagogical purposes (for my advanced students). I have also been thumbing through many of my books, which is way more fun that looking at a computer screen with decent pr0ns. Some such books: one concerning Μάχη τῶν Θερμοπυλῶν, http://www.amazon.com/Fathers-Daughters-Their-Own-Words/dp/0811806197, Sonic Warfare: Sound, Affect, and the Ecology of Fear (Technologies of Lived Abstraction) with the following review:–

“FANTASTIC BOOK” (5 Stars)

This book was published under the name of Steve Goodman (a lecturer in Music Culture at the School of Sciences, Media, and Cultural Studies at the University of East London), not of Kode9. So it is not a tutorial on how to make wobbly bass in Massive. True, because of its subject matter it can be at times heavy on the SAT phraseology, but I seriously doubt the usefulness of writing a vibrational ontology for kindergarteners, especially if that ontology is explicitly developed in the context of Leibniz, Deleuze and Guattari.

If you are looking for a fresh perspective on sonic weaponry, piracy, pop music as torture, sound systems, earworms, crowd control, and the Big Bang then this is the book for you.

If you are looking for “a pretty interesting philosophical read,” try Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations. Wait, maybe that too is “over-written,” “quickly filling and hard to digest,” so better try Martha Stewart’s Encyclopedia of Crafts: An A-to-Z Guide with Detailed Instructions and Endless Inspiration.

And if you are looking to practice your reviewing skills without having to read anything, go to Youtube and join the pissing contest coming up with the next lackluster metaphor for face-metling griminess when commenting on the latest Datsik track.

PS. Read the editorial reviews. If you feel like you don't understand them, save your money and buy instead Kode9’s Memories of the Future.

(The review is evidently responding to a troll.) At least the title of the book is honest, and the material too, though I am so dumb it is probably about how to eat recently killed game with delicacy (but no relish), on polishing Rolls Royce engines while they are running, on contradancing. I have bought 100 or so new books in the past six months, such is the intrigue I have with fonts of wisdom, the smell of paper, nice layout, always from major presses. I love books and paper and manuscripts; I used to have a part-time summer job (1998) at Houghton Library at Harvard University. That’s where the rare books and manuscripts are kept, real white glove and glass rod material.

And speaking of iDance Contra’s “canned hell”: am I, trying not to disturb nature by opening that “can of hell” by breeching Pauli’s exclusion principle, and instead being more inclusive, reading about dancing, ... censored, though, lightbulb! Something just clicked! It is popular at places like Harvard and BU because the patterns resemble predictable flow in fluid dynamics! And that is all about lovin’. Here are some pictures, and this ain’t the 1/10th of it:–

And here are some excerpts. It really must be about fluid negotiating bends and changes of diameter of pipe, kind of a Bernoulli thing. Here is part of the derivation of the Bernoulli equation for incompressible fluids:

I get a hint, looking at that, that someone likes their sativa, but seriously, like, with gravity.

http://www.cdss.org/elibrary/dart/appendix_a.htm

http://www.cdss.org/elibrary/dart/appendix_b.htm

And some incredible information about flow in contradance:–

[Retrieved from http://www.cdss.org/elibrary/dart/aesthetics_1.htm on 20110227-1914.]

AN AESTHETIC OF CONTRA DANCING

The responses given by my informants in answer to the question “What makes a good dance?” can be divided into a number of clusters of criteria, each of which I would like to discuss in some detail. These clusters include the “flow” of the dance, the choice of figures and formations used in the choreography, the complexity of the dance, the social interaction that takes place within the dance, the degree to which the dance moves conform to the expectations of the dancers, the fit of the dance to the music, the physical activity level of the dance, and the quality of specialness or uniqueness exhibited by a dance.

FLOW

The most common short response to the question, “What makes a good dance?” was “good flow.” The concept of “flow” seems to refer predominantly to the transitions between the dance figures rather than to the figures themselves, and it relates to how smooth these transitions feel to the dancers. Here are two summary statements from my informants that give an idea of what is meant by this term, “flow”:

Good flow means that each transition is easily maneuvered and rewardingly maneuvered. (Jennings 1990b)

If the dance is smooth, it means that the transition from one figure to the next is easy to achieve. You do not ever have to turn the hard way. You don’t ever have to stop, literally stop in your tracks, and backtrack to do something else. Everything flows into the next thing, so you are eternally walking forward. (Park 1990)

The term “flow,” as used by my informants, has both physical qualities which have to do with the laws of physics, and nonphysical qualities which have to do with the expectations of the dancers and the degree to which they perceive the dance as “making sense.”

The physical component of “flow” concerns the motion of the body. In a dance with good flow the dance sequence avoids transitions where the dancer must change his or her momentum suddenly through either a change of direction or a change of dancing speed. (“Suddenly” is an important qualification, since many dances have either a full stop, or an assisted change of direction through an “allemande” or other strongly connected figure performed with another dancer.) If such a change of momentum is easily anticipated and can be done comfortably, it may not disrupt the flow of a dance. An example of a comfortable change of momentum might be the change from a “circle left” to a “circle right,” a transition which is common and anticipated and for which dancers have learned to adjust their footwork to make it smooth. An example of an uncomfortable change of momentum might be an “allemande left” followed by a “circle left,” in which the dancers must change from a forward counterclockwise motion to a sideways clockwise motion, requiring both a change of body position and a change of direction. Bad flow may also result from movements that are difficult because the hand that is needed is not free. Steve Zakon gives an example:

We just finished a “swing,” now the men allemande right. Well where’s your hand at the end of the “swing?” It’s behind the lady. You can’t get there. (Zakon 1990)

...

It is possible to have too much flow in a dance, especially when the choreographic sequence includes a lot of circular motion. A dance with too much flow can leave the dancers either disoriented or dizzy. Ted Sannella comments on this phenomenon:

...

In the composing of contra dances with good flow, conservation of momentum is an important principle. The movements work better when one takes advantage of the momentum already established in a previous figure, because the dancers do not have to work as hard to perform the dance. In particular, when rotating figures move into other rotating figures, the direction of rotation should not be reversed. Gene Hubert elaborates:

If you’re going to have a circle on either side of an “allemande right,” it should be a clockwise circle, which means “circle left”.... And “allemande left” means that you’re going around the other direction, which is basically “circle right” direction. So “allemandes” and “circles” work together that way.... And “swings” to “circles” and “circles” to “swings” are the same deal. A “left circle” is a basically clockwise movement, and a “swing” is a clockwise movement. They go together real naturally. (Hubert 1990b)

The conservation of angular momentum may produce acceleration and deceleration within the dance. For example, going from a “circle” into a “swing” involves an acceleration of movement, because as two dancers pull closer together for the “swing,” the conservation of momentum results in their going faster, an exciting and pleasing effect.

One way for the dancers to change directions without disrupting the flow of the dance is to use assisted changes of direction, as noted above. An “allemande,” for example, can be used to send two dancers in the opposite directions from which they came, without their having to stop or turn around. Dan Pearl gives an example:

”Anniversary Reel” by Ted Sannella has a deal where the actives go down the center while the inactives come up the center, and you allemande with your next neighbor by the handy hand, and you immediately return to your original neighbor. So it’s like you’re using the next one in line like a pole.... It’s an assisted change of direction, and that kind of muscle tension in contra dancing is fun. (Pearl 1990)

The dance composer must be careful in the use of the directions “right” and “left” if the dance is to flow well. If many dancers are doing a movement together it is not likely to be confusing, but if a single dancer must make a split-second decision between right and left, some dancers will be confused, and the flow of the dance will be disrupted by their hesitation. John Krumm has noticed this problem:

I find there’s a lot of right and left anxiety on the dance floor, a lot more than anybody imagines there is.... Thirty percent of the dance floor will be confused by simple right and left hand things. They’ll have to think. If you put right and left together a few times in one sentence, you can confuse fifty percent of the floor. Or if you have different things doing right and left, like put your left hand on your right shoulder and face left, then you confuse almost everybody. (Krumm 1990)

Another guideline offered for the composing of dances with good flow is that the last move of a dance must flow well into the first move. This is because when the dance is actually performed by the dancers, the dance is repeated perhaps fifteen times, and the transition from the last move to the first one becomes just as important as any of the other transitions. Ted Sannella emphasizes this point:

People, when they’re writing a dance, sometimes they start at the top and they go to the end. And they don’t think about what happens when you go from the end to the beginning again. You may have a dance that flows beautifully all the way through until you get to the end, and then the last figure doesn’t flow into the beginning again for the next repeat. (Sannella 1990a)

The last principle of flow discussed by my informants comes out of the problem of too much flow discussed above. In order to avoid a dance being disorienting or dizzy, the dance composer needs to insert moves which do not revolve, to break up the circular flow of a dance which contains a lot of “swings” and “circles.” Straight line movements such as the “forward and back” figure or a “down the center and back” figure will serve to break up a dizzying circular flow, as will any kind of “balance” figure.

[Retrieved from http://www.cdss.org/elibrary/dart/changes.htm on 20110227-1907.]

TABLE 2. CHANGES IN CONTRA DANCE CHOREOGRAPHY

FORMATIONS:

1. The triple formation and the proper formation are used less frequently.

2. The improper formation and the Becket formation are most commonly used.

SYMMETRICAL ROLES:

1. There is less distinction between the roles of the active and inactive couples.

2. Terminology has been altered to reflect this change.

FIGURES:

1. The use of the “swing” has increased.

2. Fractional figures are common.

3. Figures danced on the diagonal are being used.

4. Borrowed and invented figures have been added to the repertoire.

5. “No hands” figures have become more popular.

6. Strongly connected figures are used to facilitate good flow.

7. The use of figures requiring unequal roles has declined.

TRANSITIONS:

1. The sequence “down the center and back” and “cast off” has declined in use.

2. Figures that cross the set and return are now used more often in their half form.

3. Transitions are designed to build momentum for vigorous dancing.

COMPLEXITY:

1. Sequences are more complex.

2. Figures of shorter duration are common.

3. Dance movements are faster and use closer timing.

MULTIPLE PROGRESSIONS AND END EFFECTS:

1. Dances have been composed that progress the dancers more than one place in a single round of the dance.

2. Both single and multiple progression dances may require dancers to dance outside their minor set of two couples.

3. More complicated choreography has resulted in more complex adjustments that must be made at the ends of the set.

NUMBERS OF DANCES:

There are many more dances in circulation now.

******

I have so many books to write about, and interests, now that I made a major breakthrough. It might just be a TP in my ~life. I talked about TP in this blog or the other. And, especially pertinent....

I see the Coen brothers have a new cinematic experience awaiting me. Yes, just for me. No Country for Old Men was quite something. From Wikipedia (yawn):–

Javier Bardem as Anton Chigurh, a hitman hired to recover the missing money. The character was a recurrence of the “Unstoppable Evil” archetype found in the Coen brothers’ work, though the brothers wanted to avoid one-dimensionality, particularly a comparison to The Terminator.[7] The Coen brothers sought to cast someone “who could have come from Mars” to avoid a sense of identification. The brothers introduced the character in the beginning of the film in a manner similar to the opening of the 1976 film The Man Who Fell to Earth.[8] Chigurh has been perceived as a “modern equivalent of Death from Ingmar Bergman's 1957 film The Seventh Seal.”[9] Chigurh's distinctive look was derived from a 1979 photo from a book supplied by Jones which featured photos of brothel patrons on the Texas-Mexico border.[10] After seeing himself with the new hairdo for the first time, Bardem reportedly said, “I’m not going to be laid for three months.” Bardem signed on because he had been a Coens’ fan ever since he saw their debut, Blood Simple.[11]

The latter film is one of my favorite films ever, and I think while watching (it for the tenth time) that I received my first success handjob. Quite startling. Closely behind Blood Simple is the candid O Brother, Where Art Thou?. I would certainly not label it a comedy. And, yes, the parallels with Homer’s Odyssey are in plain sight. I am sure many people say that. I bet many of them haven’t read Homer’s Odyssey, even in translation. They might just know about Circe, the Sirens, Calypso, and Trojan Horses. No, that’s the Iliad.

On my other blog I am singing of song, about